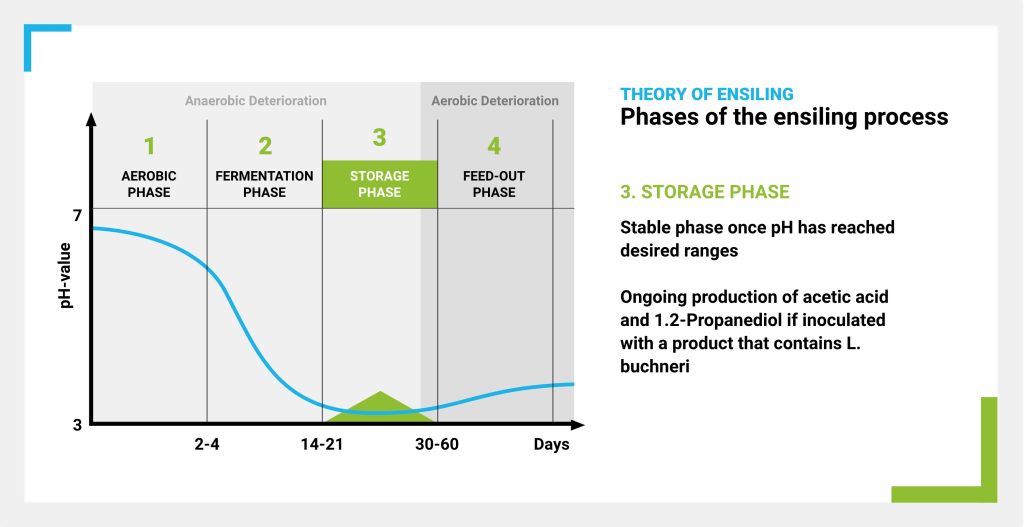

The Four Stages Of Ensiling

We talk a lot about ensiling around here, and rightfully so. It’s one of the more vital parts of the farm, because the ensiling process directly impacts the health of your animals. Improper ensiling can mean that your cows don’t get the nutrients they need, which makes for unhappy cows and reduced production.

But how does the process work?

Once your silage is ensiled, what happens in that (usually) 6-8 week period that makes it healthy food for your animals? We’ll explain by breaking it down into 4 phases.

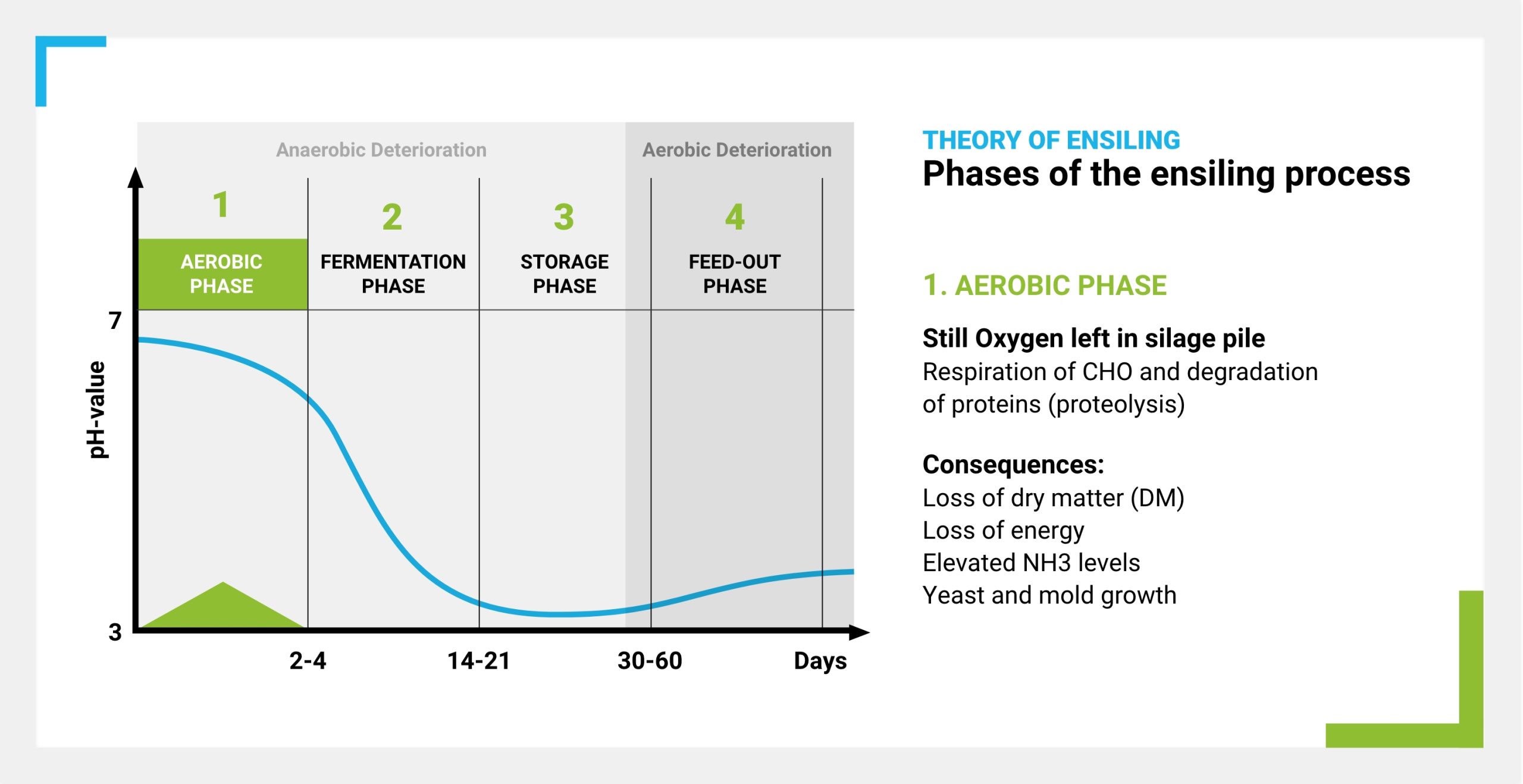

1. Aerobic Phase

This takes place in the first 2-4 days after ensiling. Ideally, at the end of this phase, all the oxygen has been used up by microorganisms in the silage. If oxygen remains in the pile, you might be losing dry matter and energy, while yeast and mold become a risk.

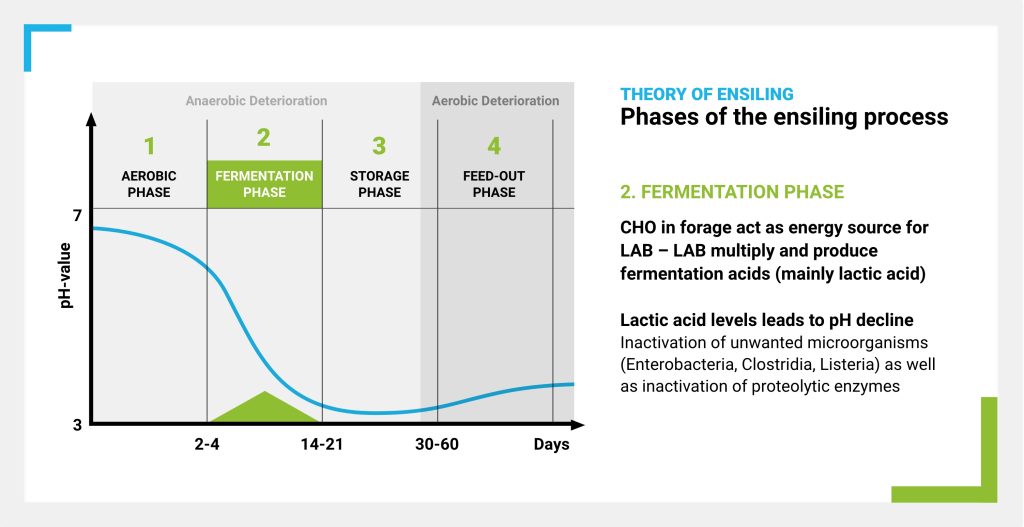

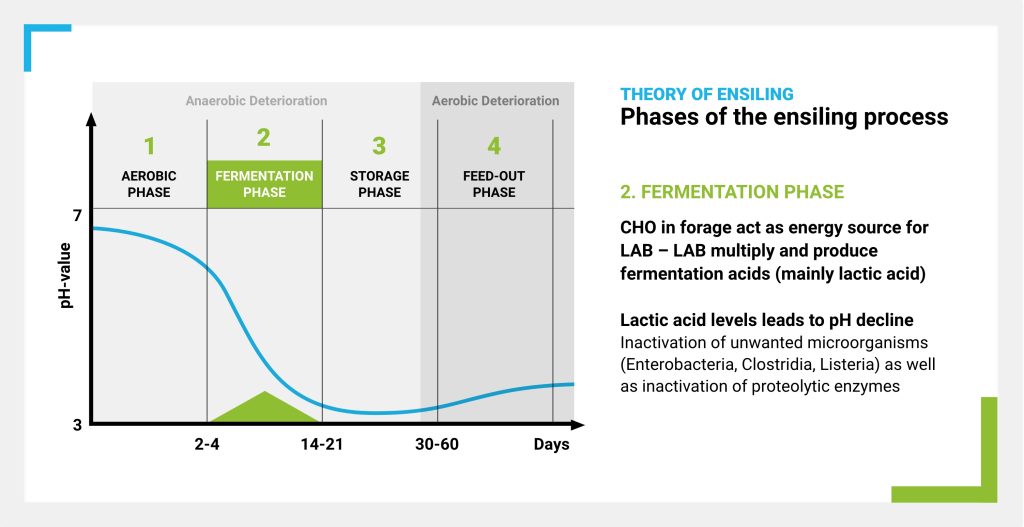

2. Fermentation Phase

From about 4 – 14 days after covering, fermentation is in full effect. Lactic acid and acetic acid are building up, which leads to a drop in pH, so that fermentation can do what it needs to do. For corn, you want your pH value to be lower than 4.2 during this phase. For grass, lower than 4.8 is acceptable. If your pH is too high, fermentation may slow and “spoilage” microbes can cause yeast and mold to take hold.

3. Storage Phase

Starting at around 2-3 weeks, the storage phase begins, assuming your pH is stable. Fermentation slows to a crawl and everything under the tarp remains stable. Acetic acid is still being produced and the temperature, if the pile is inoculated properly, will drop. If the fermentation went well in the previous phase, lactic acid should be the majority of your fatty acid content. The most important part of this phase is keeping oxygen from entering the pile. If oxygen gets in, yeast and mold will grow and your dry matter content can take a major hit.

4. Feedout Phase

Once you’re sure the pile is stable and your dry-matter content is right, you can open the pile. This can take place 6-8 weeks after initial silage. Obviously, you’re exposing your silage to oxygen at this point which comes with inherent risks. Yeast and mold activity can spike, leading to a kickstart of the fermentation process and spoilage, not to mention a major loss of nutritional value of the silage. Proper amounts of acetic acid can prevent this “re-heating” from taking place and maintain the nutritional value and dry matter content that your cows require.